Take, for example, following code chunk and read it aloud:

iris %>%

subset(Sepal.Length > 5) %>%

aggregate(. ~ Species, ., mean)

You're right, the code chunk above will translate to something like "you take the Iris data, then you subset the data and then you aggregate the data".

This is one of the most powerful things about the Tidyverse. In fact, having a standardized chain of processing actions is called "a pipeline". Making pipelines for a data format is great, because you can apply that pipeline to incoming data that has the same formatting and have it output in a

ggplot2

friendly format, for example.

R is a functional language, which means that your code often contains a lot of parenthesis,

(

and

)

. When you have complex code, this often will mean that you will have to nest those parentheses together. This makes your R code hard to read and understand. Here's where

%>%

comes in to the rescue!

Take a look at the following example, which is a typical example of nested code:

# Initialize `x`

x <- c(0.109, 0.359, 0.63, 0.996, 0.515, 0.142, 0.017, 0.829, 0.907)

# Compute the logarithm of `x`, return suitably lagged and iterated differences,

# compute the exponential function and round the result

round(exp(diff(log(x))), 1)

With the help of

%<%

, you can rewrite the above code as follows:

# Import `magrittr`

library(magrittr)

# Perform the same computations on `x` as above

x %>% log() %>%

diff() %>%

exp() %>%

round(1)

Note

that you need to import the

magrittr

library

to get the above code to work. That's because the pipe operator is, as you read above, part of the

magrittr

library and is, since 2014, also a part of

dplyr

. If you forget to import the library, you'll get an error like

Error in eval(expr, envir, enclos): could not find function "%>%"

.

Also note that it isn't a formal requirement to add the parentheses after

log

,

diff

and

exp

, but that, within the R community, some will use it to increase the readability of the code.

In short, here are four reasons why you should be using pipes in R:

These reasons are taken from the

magrittr

documentation itself

. Implicitly, you see the arguments of readability and flexibility returning.

Even though

%>%

is the (main) pipe operator of the

magrittr

package, there are a couple of other operators that you should know and that are part of the same package:

%<>%

;

# Initialize `x`

x <- rnorm(100)

# Update value of `x` and assign it to `x`

x %<>% abs %>% sort

%T>%

;

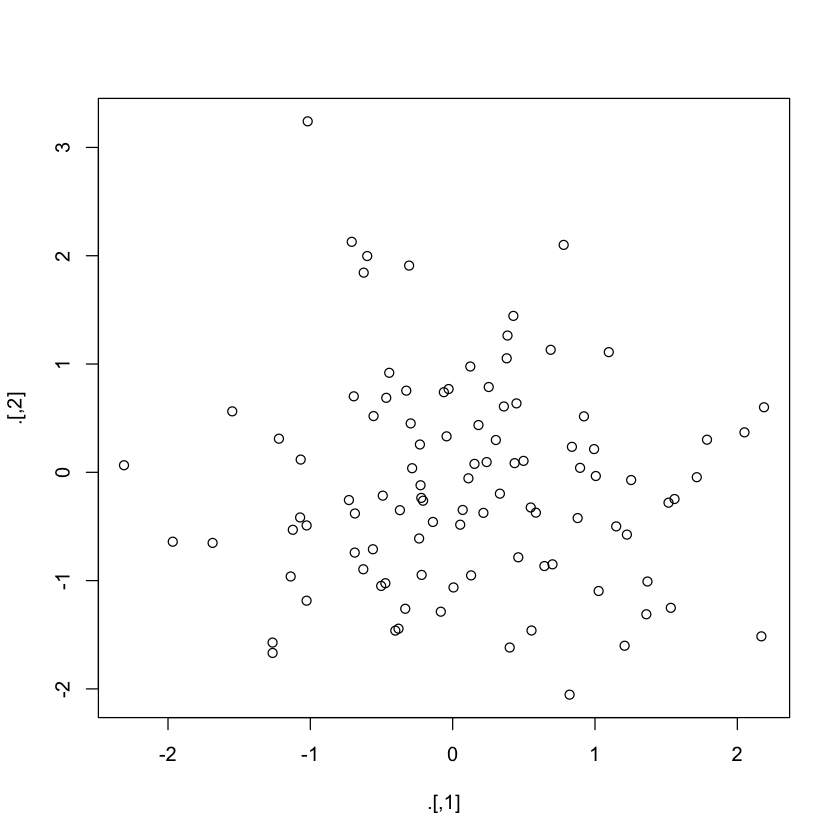

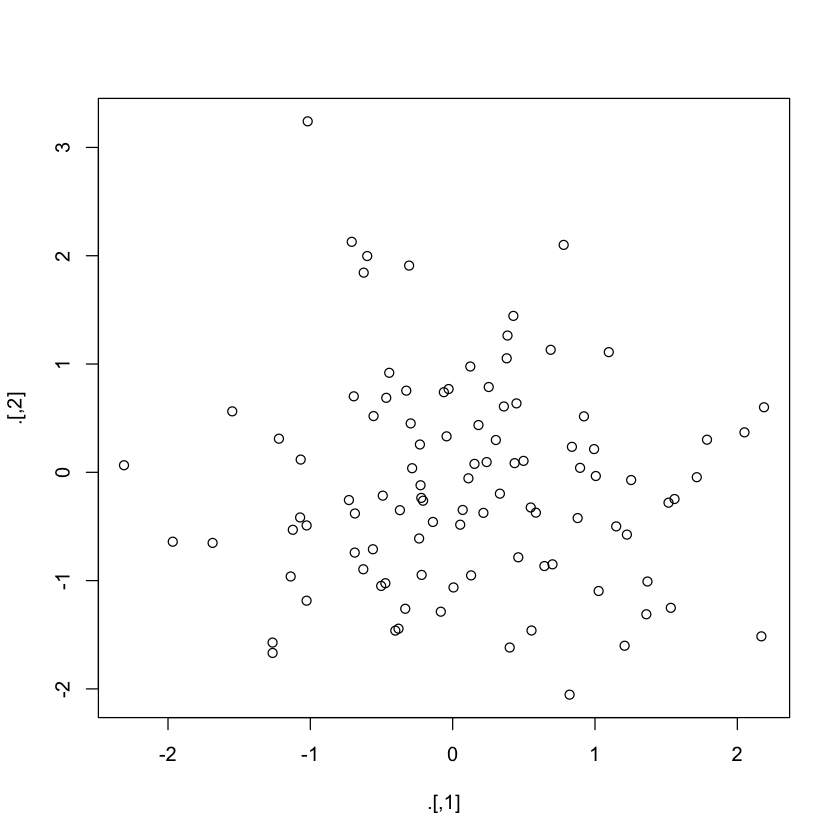

rnorm(200) %>%

matrix(ncol = 2) %T>%

plot %>%

colSums

Note that it's good to know for now that the above code chunk is actually a shortcut for:

rnorm(200) %>%

matrix(ncol = 2) %T>%

{ plot(.); . } %>%

colSums

But you'll see more about that later on!

%$%

.

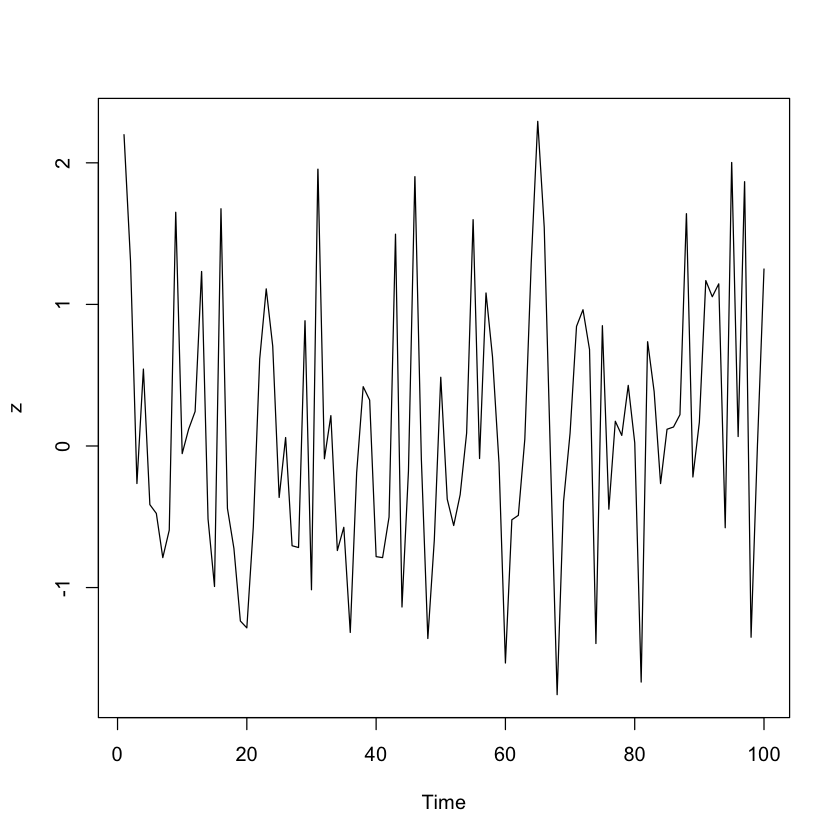

data.frame(z = rnorm(100)) %$%

ts.plot(z)

Of course, these three operators work slightly differently than the main

%>%

operator. You'll see more about their functionalities and their usage later on in this tutorial!

Note

that, even though you'll most often see the

magrittr

pipes, you might also encounter other pipes as you go along! Some examples are

wrapr

's dot arrow pipe

%.>%

or to dot pipe

%>.%

, or the

Bizarro pipe

->.;

.

Now that you know how the

%>%

operator originated, what it actually is and why you should use it, it's time for you to discover how you can actually use it to your advantage. You will see that there are quite some ways in which you can use it!

Before you go into the more advanced usages of the operator, it's good to first take a look at the most basic examples that use the operator. In essence, you'll see that there are 3 rules that you can follow when you're first starting out:

f(x)

can be rewritten as

x %>% f

In short, this means that functions that take one argument,

function(argument)

, can be rewritten as follows:

argument %>% function()

. Take a look at the following, more practical example to understand how these two are equivalent:

# Compute the logarithm of `x`

log(x)

# Compute the logarithm of `x`

x %>% log()

f(x, y)

can be rewritten as

x %>% f(y)

Of course, there are a lot of functions that don't just take one argument, but multiple. This is the case here: you see that the function takes two arguments,

x

and

y

. Similar to what you have seen in the first example, you can rewrite the function by following the structure

argument1 %>% function(argument2)

, where

argument1

is the

magrittr

placeholder and

argument2

the function call.

This all seems quite theoretical. Let's take a look at a more practical example:

# Round pi

round(pi, 6)

# Round pi

pi %>% round(6)

x %>% f %>% g %>% h

can be rewritten as

h(g(f(x)))

This might seem complex, but it isn't quite like that when you look at a real-life R example:

# Import `babynames` data

library(babynames)

# Import `dplyr` library

library(dplyr)

# Load the data

data(babynames)

# Count how many young boys with the name "Taylor" are born

sum(select(filter(babynames,sex=="M",name=="Taylor"),n))

# Do the same but now with `%>%`

babynames%>%filter(sex=="M",name=="Taylor")%>%

select(n)%>%

sum

Note

how you work from the inside out when you rewrite the nested code: you first put in the

babynames

, then you use

%>%

to first

filter()

the data. After that, you'll select

n

and lastly, you'll

sum()

everything.

Remember

also that you already saw another example of such a nested code that was converted to more readable code in the beginning of this tutorial, where you used the

log()

,

diff()

,

exp()

and

round()

functions to perform calculations on

x

.

Unfortunately, there are some exceptions to the more general rules that were outlined in the previous section. Let's take a look at some of them here.

Consider this example, where you use the

assign()

function to assign the value

10

to the variable

x

.

# Assign `10` to `x`

assign("x", 10)

# Assign `100` to `x`

"x" %>% assign(100)

# Return `x`

x

10

You see that the second call with the

assign()

function, in combination with the pipe, doesn't work properly. The value of

x

is not updated.

Why is this?

That's because the function assigns the new value

100

to a temporary environment used by

%>%

. So, if you want to use

assign()

with the pipe, you must be explicit about the environment:

# Define your environment

env <- environment()

# Add the environment to `assign()`

"x" %>% assign(100, envir = env)

# Return `x`

x

100

Arguments within functions are only computed when the function uses them in R. This means that no arguments are computed before you call your function! That means also that the pipe computes each element of the function in turn.

One place that this is a problem is

tryCatch()

, which lets you capture and handle errors, like in this example:

tryCatch(stop("!"), error = function(e) "An error")

stop("!") %>%

tryCatch(error = function(e) "An error")

'An error'

Error in eval(expr, envir, enclos): !

Traceback:

1. stop("!") %>% tryCatch(error = function(e) "An error")

2. eval(lhs, parent, parent)

3. eval(expr, envir, enclos)

4. stop("!")

You'll see that the nested way of writing down this line of code works perfectly, while the piped alternative returns an error. Other functions with the same behavior are

try()

,

suppressMessages()

, and

suppressWarnings()

in base R.

There are also instances where you can use the pipe operator as an argument placeholder. Take a look at the following examples:

f(x, y)

can be rewritten as

y %>% f(x, .)

In some cases, you won't want the value or the

magrittr

placeholder to the function call at the first position, which has been the case in every example that you have seen up until now. Reconsider this line of code:

pi %>% round(6)

If you would rewrite this line of code,

pi

would be the first argument in your

round()

function. But what if you would want to replace the second, third, ... argument and use that one as the

magrittr

placeholder to your function call?

Take a look at this example, where the value is actually at the third position in the function call:

"Ceci n'est pas une pipe" %>% gsub("une", "un", .)

'Ceci n\'est pas un pipe'

f(y, z = x)

can be rewritten as

x %>% f(y, z = .)

Likewise, you might want to make the value of a specific argument within your function call the

magrittr

placeholder. Consider the following line of code:

6 %>% round(pi, digits=.)

It is straight-forward to use the placeholder several times in a right-hand side expression. However, when the placeholder only appears in a nested expressions

magrittr

will still apply the first-argument rule. The reason is that in most cases this results more clean code.

Here are some general "rules" that you can take into account when you're working with argument placeholders in nested function calls:

f(x, y = nrow(x), z = ncol(x))

can be rewritten as

x %>% f(y = nrow(.), z = ncol(.))

# Initialize a matrix `ma`

ma <- matrix(1:12, 3, 4)

# Return the maximum of the values inputted

max(ma, nrow(ma), ncol(ma))

# Return the maximum of the values inputted

ma %>% max(nrow(ma), ncol(ma))

12

12

The behavior can be overruled by enclosing the right-hand side in braces:

f(y = nrow(x), z = ncol(x))

can be rewritten as

x %>% {f(y = nrow(.), z = ncol(.))}

# Only return the maximum of the `nrow(ma)` and `ncol(ma)` input values

ma %>% {max(nrow(ma), ncol(ma))}

4

To conclude, also take a look at the following example, where you could possibly want to adjust the workings of the argument placeholder in the nested function call:

# The function that you want to rewrite

paste(1:5, letters[1:5])

# The nested function call with dot placeholder

1:5 %>%

paste(., letters[.])

You see that if the placeholder is only used in a nested function call, the

magrittr

placeholder will also be placed as the first argument! If you want to avoid this from happening, you can use the curly brackets

{

and

}

:

# The nested function call with dot placeholder and curly brackets

1:5 %>% {

paste(letters[.])

}

# Rewrite the above function call

paste(letters[1:5])

Unary functions are functions that take one argument. Any pipeline that you might make that consists of a dot

.

, followed by functions and that is chained together with

%>%

can be used later if you want to apply it to values. Take a look at the following example of such a pipeline:

. %>% cos %>% sin

This pipeline would take some input, after which both the

cos()

and

sin()

fuctions would be applied to it.

But you're not there yet! If you want this pipeline to do exactly that which you have just read, you need to assign it first to a variable

f

, for example. After that, you can re-use it later to do the operations that are contained within the pipeline on other values.

# Unary function

f <- . %>% cos %>% sin

f

structure(function (value)

freduce(value, `_function_list`), class = c("fseq", "function"

))

Remember

also that you could put parentheses after the

cos()

and

sin()

functions in the line of code if you want to improve readability. Consider the same example with parentheses:

. %>% cos() %>% sin()

.

You see, building functions in

magrittr

very similar to building functions with base R! If you're not sure how similar they actually are, check out the line above and compare it with the next line of code; Both lines have the same result!

# is equivalent to

f <- function(.) sin(cos(.))

f

function (.)

sin(cos(.))

There are situations where you want to overwrite the value of the left-hand side, just like in the example right below. Intuitively, you will use the assignment operator

<-

to do this.

# Load in the Iris data

iris <- read.csv(url("http://archive.ics.uci.edu/ml/machine-learning-databases/iris/iris.data"), header = FALSE)

# Add column names to the Iris data

names(iris) <- c("Sepal.Length", "Sepal.Width", "Petal.Length", "Petal.Width", "Species")

# Compute the square root of `iris$Sepal.Length` and assign it to the variable

iris$Sepal.Length <-

iris$Sepal.Length %>%

sqrt()

However, there is a compound assignment pipe operator, which allows you to use a shorthand notation to assign the result of your pipeline immediately to the left-hand side:

# Compute the square root of `iris$Sepal.Length` and assign it to the variable

iris$Sepal.Length %<>% sqrt

# Return `Sepal.Length`

iris$Sepal.Length

Note

that the compound assignment operator

%<>%

needs to be the first pipe operator in the chain for this to work. This is completely in line with what you just read about the operator being a shorthand notation for a longer notation with repetition, where you use the regular

<-

assignment operator.

As a result, this operator will assign a result of a pipeline rather than returning it.

The tee operator works exactly like

%>%

, but it returns the left-hand side value rather than the potential result of the right-hand side operations.

This means that the tee operator can come in handy in situations where you have included functions that are used for their side effect, such as plotting with

plot()

or printing to a file.

In other words, functions like

plot()

typically don't return anything. That means that, after calling

plot()

, for example, your pipeline would end. However, in the following example, the tee operator

%T>%

allows you to continue your pipeline even after you have used

plot()

:

set.seed(123)

rnorm(200) %>%

matrix(ncol = 2) %T>%

plot %>%

colSums

When you're working with R, you'll find that many functions take a

data

argument. Consider, for example, the

lm()

function

or the

with()

function

. These functions are useful in a pipeline where your data is first processed and then passed into the function.

For functions that don't have a

data

argument, such as the

cor()

function, it's still handy if you can expose the variables in the data. That's where the

%$%

operator comes in. Consider the following example:

iris %>%

subset(Sepal.Length > mean(Sepal.Length)) %$%

cor(Sepal.Length, Sepal.Width)

0.336696922252551

With the help of

%$%

you make sure that

Sepal.Length

and

Sepal.Width

are exposed to

cor()

. Likewise, you see that the data in the

data.frame()

function is passed to the

ts.plot()

to plot several time series on a common plot:

data.frame(z = rnorm(100)) %$%

ts.plot(z)

dplyr

and

magrittr

In the introduction to this tutorial, you already learned that the development of

dplyr

and

magrittr

occurred around the same time, namely, around 2013-2014. And, as you have read, the

magrittr

package is also part of the Tidyverse.

In this section, you will discover how exciting it can be when you combine both packages in your R code.

For those of you who are new to the

dplyr

package, you should know that this R package was built around five verbs, namely, "select", "filter", "arrange", "mutate" and "summarize". If you have already manipulated data for some data science project, you will know that these verbs make up the majority of the data manipulation tasks that you generally need to perform on your data.

Take an example of some traditional code that makes use of these

dplyr

functions:

library(hflights)

grouped_flights <- group_by(hflights, Year, Month, DayofMonth)

flights_data <- select(grouped_flights, Year:DayofMonth, ArrDelay, DepDelay)

summarized_flights <- summarise(flights_data,

arr = mean(ArrDelay, na.rm = TRUE),

dep = mean(DepDelay, na.rm = TRUE))

final_result <- filter(summarized_flights, arr > 30 | dep > 30)

final_result

| Year | Month | DayofMonth | arr | dep |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2011 | 2 | 4 | 44.08088 | 47.17216 |

| 2011 | 3 | 3 | 35.12898 | 38.20064 |

| 2011 | 3 | 14 | 46.63830 | 36.13657 |

| 2011 | 4 | 4 | 38.71651 | 27.94915 |

| 2011 | 4 | 25 | 37.79845 | 22.25574 |

| 2011 | 5 | 12 | 69.52046 | 64.52039 |

| 2011 | 5 | 20 | 37.02857 | 26.55090 |

| 2011 | 6 | 22 | 65.51852 | 62.30979 |

| 2011 | 7 | 29 | 29.55755 | 31.86944 |

| 2011 | 9 | 29 | 39.19649 | 32.49528 |

| 2011 | 10 | 9 | 61.90172 | 59.52586 |

| 2011 | 11 | 15 | 43.68134 | 39.23333 |

| 2011 | 12 | 29 | 26.30096 | 30.78855 |

| 2011 | 12 | 31 | 46.48465 | 54.17137 |

When you look at this example, you immediately understand why

dplyr

and

magrittr

are able to work so well together:

hflights %>%

group_by(Year, Month, DayofMonth) %>%

select(Year:DayofMonth, ArrDelay, DepDelay) %>%

summarise(arr = mean(ArrDelay, na.rm = TRUE), dep = mean(DepDelay, na.rm = TRUE)) %>%

filter(arr > 30 | dep > 30)

Both code chunks are fairly long, but you could argue that the second code chunk is more clear if you want to follow along through all of the operations. With the creation of intermediate variables in the first code chunk, you could possibly lose the "flow" of the code. By using

%>%

, you gain a more clear overview of the operations that are being performed on the data!

In short,

dplyr

and

magrittr

are your dreamteam for manipulating data in R!

Adding all these pipes to your R code can be a challenging task! To make your life easier, John Mount, co-founder and Principal Consultant at Win-Vector, LLC and DataCamp instructor , has released a package with some RStudio add-ins that allow you to create keyboard shortcuts for pipes in R. Addins are actually R functions with a bit of special registration metadata. An example of a simple addin can, for example, be a function that inserts a commonly used snippet of text, but can also get very complex!

With these addins, you'll be able to execute R functions interactively from within the RStudio IDE, either by using keyboard shortcuts or by going through the Addins menu.

Note that this package is actually a fork from RStudio's original add-in package, which you can find here . Be careful though, the support for addins is available only within the most recent release of RStudio! If you want to know more on how you can install these RStudio addins, check out this page .

You can download the add-ins and keyboard shortcuts here .

In the above, you have seen that pipes are definitely something that you should be using when you're programming with R. More specifically, you have seen this by covering some cases in which pipes prove to be very useful! However, there are some situations, outlined by Hadley Wickham in "R for Data Science" , in which you can best avoid them:

In cases like these, it's better to create intermediate objects with meaningful names. It will not only be easier for you to debug your code, but you'll also understand your code better and it'll be easier for others to understand your code.

If you aren't transforming one primary object, but two or more objects are combined together, it's better not to use the pipe.

Pipes are fundamentally linear and expressing complex relationships with them will only result in complex code that will be hard to read and understand.

Using pipes in internal package development is a no-go, as it makes it harder to debug!

For more reflections on this topic, check out this Stack Overflow discussion . Other situations that appear in that discussion are loops, package dependencies, argument order and readability.

In short, you could summarize it all as follows: keep the two things in mind that make this construct so great, namely, readability and flexibility. As soon as one of these two big advantages is compromised, you might consider some alternatives in favor of the pipes.

After all that you have read by you might also be interested in some alternatives that exist in the R programming language. Some of the solutions that you have seen in this tutorial were the following:

Instead of chaining all operations together and outputting one single result, break up the chain and make sure you save intermediate results in separate variables. Be careful with the naming of these variables: the goal should always be to make your code as understandable as possible!

One of the possible objections that you could have against pipes is the fact that it goes against the "flow" that you have been accustomed to with base R. The solution is then to stick with nesting your code! But what to do then if you don't like pipes but you also think nesting can be quite confusing? The solution here can be to use tabs to highlight the hierarchy.

You have covered a lot of ground in this tutorial: you have seen where

%>%

comes from, what it exactly is, why you should use it and how you should use it. You've seen that the

dplyr

and

magrittr

packages work wonderfully together and that there are even more operators out there! Lastly, you have also seen some cases in which you shouldn't use it when you're programming in R and what alternatives you can use in such cases.